“Sometimes one has simply to endure a period of depression for what it may hold of illumination if one can live through it, attentive to what it exposes or demands.”

“A great deal of poetic work has arisen from various despairs,” wrote Lou Andreas-Salomé, the first woman psychoanalyst, in a consolatory letter to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke as he was wrestling with depression, nearly a century before psychologists came to study the nonlinear relationship between creativity and mental illness. A generation later, with an eye to what made Goethe a genius, Humphrey Trevelyan argued that great artists must have the courage to despair, that they “must be shaken by the naked truths that will not be comforted. This divine discontent, this disequilibrium, this state of inner tension is the source of artistic energy.”

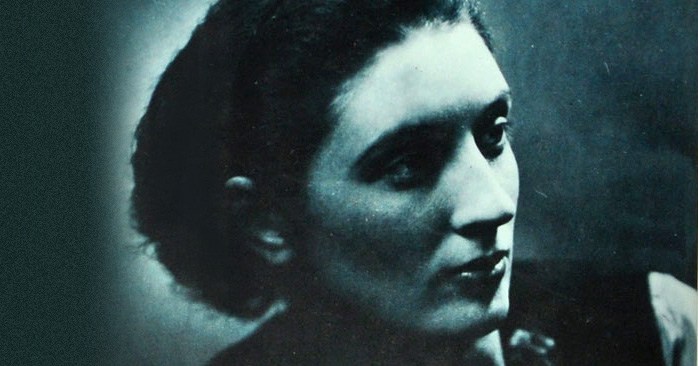

Few artists have articulated the dance between this “divine discontent” and creative fulfillment more memorably than the poet, novelist, essayist, and diarist May Sarton(May 3, 1912–July 16, 1995). In her Journal of a Solitude (public library), Sarton records and reflects on her interior life in the course of one year, her sixtieth, with remarkable candor and courage. Out of these twelve private months arises the eternity of the human experience with its varied universal capacities for astonishment and sorrow, hollowing despair and creative vitality.